Developing the Next Generation of Creative Leaders

This article was originally published in the Design Management Review in November 2015. A publication of the Design Management Institute.

You can download the full article at Wiley Publishing.

The day that I turned 18 years old, my worldview changed dramatically. That day was September 11, 2001.

Before that day, I viewed the world as big, safe, and full of opportunity. After that day, the world appeared small, scary, and lacking opportunity. This pivotal event, along with the financial crisis that began in September 2008 (the month I started my first business) and the great recession that followed have greatly influenced my perspective on the world, the problems we collectively face, and my role within it. These events represent a systemic failure in leadership and point to the fact that societal change is crucial. There’s clearly a lot of work to do.

I share my story and perspective because I believe that many people within my generation have a similar outlook on the world.

The opportunities that creativity and design represent are core components of this generational perspective. We entered the economy as design thinking became mainstream, accessible, and synonymous with problem solving. There are big challenges in the world, and we have the tools to help solve them.

Where do we start? Where we work.

The implication for organizations is huge, as this perspective shapes our views on work: what it should look like, what needs to change, and how fast this change should happen.

Organizational Tension

This new generation of creative leaders is emerging quickly. They are eager, energized, and enthusiastic to grow personally and create change, yet they often struggle to integrate into organizations. The irony is that many corporate executives and older employees struggle to utilize this young talent and harness their energy. Because of this, many organizations are stuck.

Many of the executives I talk to are frustrated that recent hires and young staff are overly eager for more responsibility, new titles, and different opportunities. Simultaneously, I hear young employees express frustration at the lack of growth opportunities, and that “things aren’t changing fast enough.”

There’s a clear tension between generations, and it stems from a differing sense of urgency, patience, and understanding the other’s perspective. In many companies, this tension is at unhealthy levels and is putting great stress on individuals and teams. Younger employees appear entitled and impatient, while older employees appear stubborn and dismissive. If it is not addressed, this stress can result in deep conflict, lack of cohesion, lost productivity, and decreased profit.

Creativity thrives within healthy levels of tension. Tension thrives whenever there are humans working together. Within the context of work, individuals and teams are at risk of burnout if that tension is not managed effectively.

The success of teams can range widely. Sometimes a team is cohesive and productive. Other times, the same team operates as if it is on the brink of collapse. People are complex, creativity can be fleeting, and the creative process can, and maybe should, be messy.

Much of my work with organizations is focused on harnessing organizational tension to increase the health conditions so that companies can innovate, transform, and grow. With organizations that are experiencing this generational tension, this looks like developing emerging leaders, helping executives understand their young talent more deeply, and designing systems to support continued learning, development, and efficiency.

Organizations that have an integrated discipline of design are uniquely positioned to leverage this tension to increase value creation and organizational capacity.

In this article, I’ve outlined three things you can do to leverage this tension and focus creative energy on improving your organization to drive innovation and growth. I use examples from my work with clients to frame what these strategies can look like.

I also use examples from the media to highlight why developing and focusing creative talent is important.

1. Embed the practice of leadership as a discipline across all levels.

My team and I recently worked with a digital creative agency that, after rapid growth, wanted to focus on efficiency and develop their talented “doers” into leaders. We delivered a custom leadership development program for more than 65 of their staff and designed strategies to integrate leadership as a discipline into their organizational architecture.

I’ve seen the practice of leadership have a major impact on the collective output of teams and the financial and cultural health of companies. This impact is most visible within the interactions and relationships between individual team members and is made possible by a healthy environment that supports the creative process.

Here’s an analogy I like to use:

- Think about a creative team as a brain and each member of the team as individual neurons.

- Neurons communicate by sending signals through synapses—junctions or pathways between cells. Consider these synapses to be the relationships among team members, and each signal sent as individual interactions. To communicate effectively through its synaptic pathways, each neuron must be adequately nourished and must exist in a healthy environment.

- It’s been widely proposed that omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish oil) are essential for helping to produce and maintain a healthy brain. They provide neurons and synapses with the nourishment required to function. By consuming omega-3s, we are helping to create a healthy environment that allows for our neurons to communicate effectively, which leads to increased cognitive capacity and greater function.

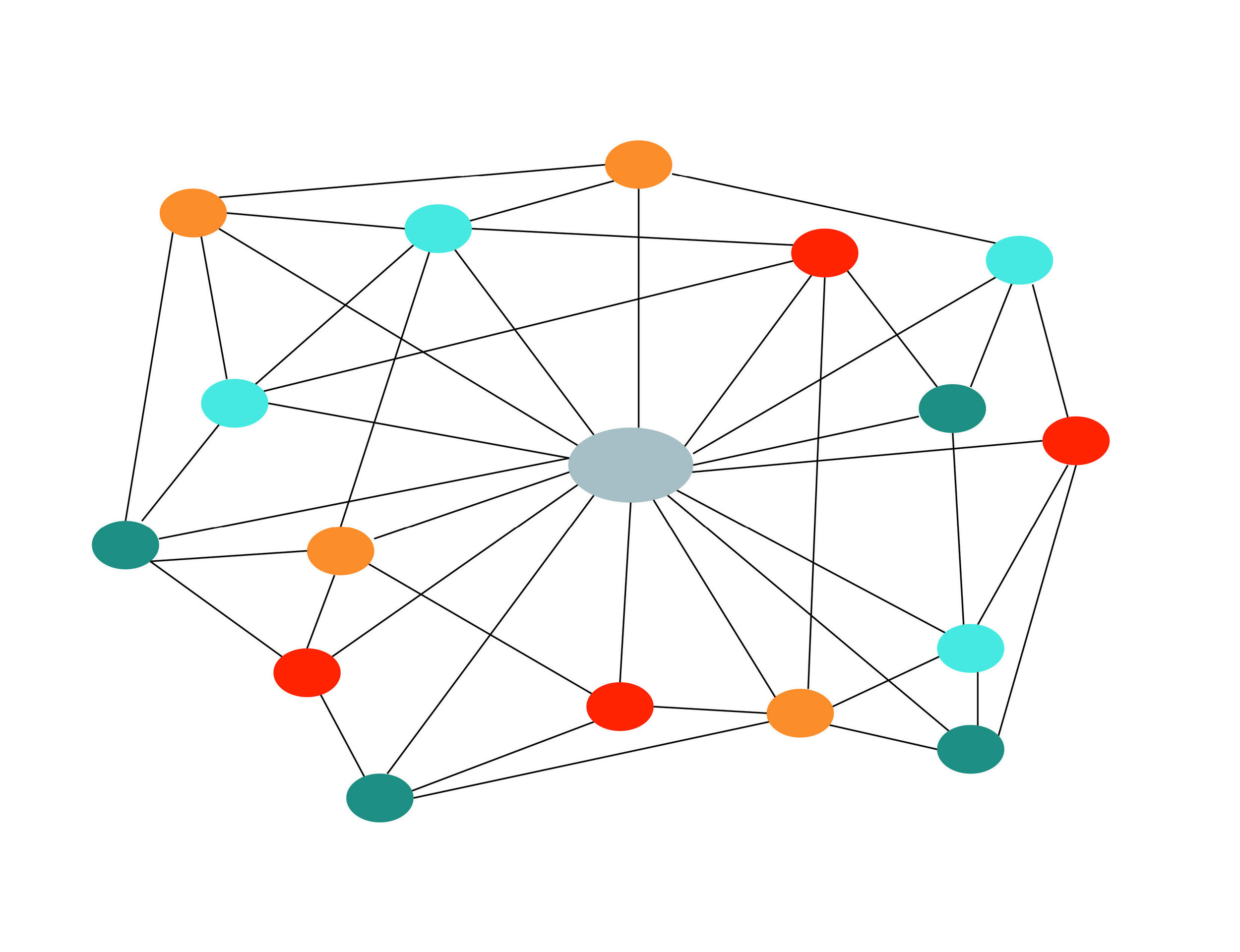

Figure 1: A simple representation of a team with individual team members in various colors having different levels of leadership capacity. The grey center represents the collective output of the team.

Let’s think about this in terms of the practice of leadership within a team.

I define the practice of leadership as the act of increasing your capacity to understand yourself, your relationships, and the context in which you operate in order to influence each of those things in a generative way.

Simplified, this looks like: Understanding × Influence = Leadership capacity

Figure 2: This formula can be translated into a simple 2x2 matrix. The horizontal axis represents capacity to understand and the vertical axis represents capacity to influence. Optimal leadership capacity is pictured in blue in the upper right quadrant.

The more capacity that each team member has to understand and influence, the stronger the practice of leadership is within a team, and the healthier the environment becomes. If the environment is healthy, the relationships between people are stronger. If relationships are strong, each interaction will be more effective. And, it's cyclical over time. As each interaction becomes more effective, the capacity for each individual to understand and influence increases, and so on...

As with the topic of millennials in the workforce, there’s an incredible amount of information and literature on leadership. Some of it is excellent. Some not. Much of it is focused on traits and qualities that represent a steady state of “being a leader” and is modeled after what leadership has looked like in the past. This can be dangerous, specifically as it relates to diversity within organizations.

After the US men’s soccer team beat Ghana in last year’s World Cup, Delta Airlines posted a photo on twitter of the Statue of Liberty overlaid by the number 2 next to a giraffe overlaid with the number 1 to represent the final score of the match. Cue Twitter backlash pointing out the fact that giraffes do not live in Ghana.

As a result of this incident, Delta was accused of being everything from laughably naive to blatantly racist. I don’t know what Delta's intent was in posting the photo, nor do I have intimate knowledge of their internal process for vetting social media posts. I do know that it was ignorant, offensive to many people, damaging to their brand, and completely avoidable.

It’s through the practice of leadership that you develop a critical aspect of your leadership capacity: your voice.

Your voice is what you choose to express to others. It’s based on your story and your perspective. You see, feel, hear, and perceive things. You learn things over time. You build knowledge and form your worldview. This is what informs your voice. As you form and understand your perspective, it’s your responsibility to find the most authentic, appropriate, engaging, and effective way to share it with others.

Keeping the concept of voice in mind, there are three scenarios that might have allowed Delta Airlines to post this photo:

- No one who was responsible for creating and publishing this content knew that giraffes do not live in Ghana and that this post might be offensive.

- Someone did know that giraffes do not live in Ghana and that the post might be offensive—and didn’t speak up.

- Someone did know, and did speak up, but was disregarded.

Each of these scenarios is dangerous, and each points to probable systemic challenges at Delta:

- There is a lack of contextual understanding. It’s really important that your team have the contextual understanding of your organization and the market it serves. (Delta flies to Accra, Ghana.)

- Certain individuals lack the capacity to speak up when necessary. It’s critical that your team members speak up. This responsibility falls on each individual as well as the team, collectively.

- There is a lack of regard for certain voices on the team. It’s crucial that all voices on a team are heard. It’s in the best interest of those who are tasked with making decisions to listen to the voices in the room.

In a diverse and complex world, creativity and innovation depend on diverse and complex perspectives that are voiced and regarded. The success of teams depends on the ability of individuals to understand and influence.

Figure 3: The same simple team representation is updated to show increased collective output as a result of each individual team member having increased leadership capacity.

Your organization’s ability to innovate and grow is directly reliant on the health of your teams and their capacity to effectively communicate and produce. You can take an Omega-3 supplement once in a while—it won’t do much for you. You can engage your teams in a leadership workshop once in a while—the same is true. The long-term health benefits of integrating foods that are rich in Omega-3s into your diet will have a tangible effect on your health and well-being. The same is true if you can establish leadership as a discipline that is consistently practiced and that permeates every function of your company.

By making leadership a practice that everyone has access to, you’re giving young talent the time, space, and capacity to understand the organization and influence its direction in a more focused and productive way. Consider leadership development within your organization to be as essential as the development of technical skills, the adoption of new technologies, and the efficient management of projects.

2. Actively develop young employees to accelerate organizational learning.

Start developing the capacity of your young employees early. The competencies that come from a disciplined practice of leadership and personal development are critical at any stage of a career and will increase the efficiency and focus of teams. Engage your young employees in dialogue and with coaching and encourage them to develop and refine their understanding of themselves, others, and the organizational context.

There are four elements that I believe every emerging leader, and every young employee, must define:

Your values serve as a foundation. On your path, they allow you to walk on solid ground. It feels good when we live through them, it feels terrible when we act outside of them, and we often feel tension with others when they act against them in our presence. You can also think of your values as an operating procedure. If you were going into a difficult situation, what would it look like to handle the situation by behaving according to your values?

Voice begins with your unique story and your perspective on the world. We take in information through our senses; we see, we feel, we perceive things, and all of our past and present experiences inform our unique perspectives. Once you understand your perspective, you have the opportunity and responsibility to find the most authentic, appropriate, engaging, and effective way to share it with others. It’s critical to teams and organizations that a diversity of perspectives is heard and informs the way they operate and the work they produce.

Vision is what you literally see as well as what you can imagine as possibility. Think of your vision as the horizon line. It gives us our sense of place and allows us to imagine what can be. It’s important to that you allow your vision to be outside of your current reality— don’t limit yourself by what you think to be possible based on immediate restraints. A tool for defining your vision is the use of boundaries. If you feel stuck or are unsure where to start, put some boundaries of time and context around your imagination—the boundary of one year, for example. Defining your vision is an ongoing practice. The key is to imagine and then act, imagine, and act again.

Your purpose is what gets you out of bed in the morning and what keeps you moving. Purpose is closely tied to vision, and it's the relationship between the two that's important. Vision is what you’re working towards; purpose is why that is important to you. Purpose gives you your minimum viable product—meaning that while your vision will take time to build, a clear purpose will allow you to take action immediately.

When young employees have a deeper understanding of these four elements, the organization benefits. These elements exist at the organizational level too. As employees define these elements for themselves, they gain a deeper understanding of their place within the organization. I’ve seen this result in staff being reenergized and integrating more fully into the organization and I’ve also seen employees realize that they are not a good fit and leave. In either scenario, the organization benefits from increased cohesion and focus.

To ensure that the connection between personal and organizational perspective is made, it’s important to create opportunities to share and direct this understanding within the context of the company. Make sure that individual development is complimented by group learning and shared application.

3. Focus creative tension by forming “special ops” teams to make organizational improvements.

A cultural attribute of the graduate program I attended, that I love, is the concept that a complaint is a commitment. Meaning that if you see something that can be improved and you bring it up to the community, you’ve just volunteered to form a team to do something about it.

A critical stress point in the tension between generations is that young employees want to have an effect on the organization from the very beginning, while many older employees have worked their way up in the structure and have assumed responsibility over time. These are two mental models that seem to be at odds with one another. They don’t have to be.

Let’s go back to the client I mentioned earlier in this article. We found that within that organization, there had been some grumblings about the “employee experience.” To address this, we formed a “special ops” team comprised of employees who were frustrated as well as some that were not. They all had different roles within the organization, and didn’t normally have the opportunity to work together.

This strategy served multiple purposes:

- To focus their personal and collective tension on problem-solving

- To understand other people’s experiences and break out of their individual perspectives

- To develop and refine their abilities to pitch ideas to executives in the firm

Using UX design tools, the team interviewed a range of current and past employees and mapped an “employee journey.” They discovered that, depending when someone was hired; there was sometimes a gap of 1-3 months between his or her first day and when they were given important information that related to the culture of the company. This led to a lack of cohesion and a feeling of disconnection for some employees.

One strategy that came out of the work of this special ops team was to develop a mentor program that was part of the “onboarding” process. Each new employee is now assigned a peer mentor from within the company, who meets with him or her on that first day to help the new employee better understand the organization. Not only does this help to integrate new hires into the organizational culture, but it also serves to reinforce important aspects of the company with long-standing employees.

For those who participated on the special ops team, this activity produced a deeper understanding of themselves, other people on staff, and the organizational context, and it created an outlet for people’s energy that could otherwise have resulted in conflict or attrition.

Another example of this approach was with a retail client. During the holiday season, the busiest time of the year, we formed a special ops team to observe where breakdowns were occurring. We met weekly for two hours, outside of the store, to share thoughts and have dialogue on what was observed. During the holiday season, the expectation of this team was to not develop solutions immediately but to collect information that would help redesign systems when we knew that business would slow down and there would be time and capacity to focus on designing solutions. There was significant stress among some employees that was caused by the sense that things were not working as well as they could be and that there was not time or capacity to do anything about it. This team’s focus was to first ‘problem find’ and then, problem solve. After the holiday season, they refocused on designing solutions for what was observed.

This approach provided the opportunity for younger employees to learn the value of understanding challenges on a deeper level before designing solutions. Meeting outside of normal business hours and in a different space allowed for the team to understand one another better and for newer staff to develop their voice and share their perspective in ways were not possible while they were “at work.” The focused scope and schedule constraints helped to ease tension among employees who believed that every challenge should be solved immediately.

Organizational tension is a powerful force that when focused can improve systems and increase employee engagement. Creating special ops teams that encourage deeper understanding and focused problem solving is an effective strategy to do this.

Conclusion

There’s an emerging generation of creative talent that is driven to improve the world - starting with where they work. Let them. Your organization will benefit.

While this urgency to improve and develop can cause tension among staff, executives have the opportunity to leverage intergenerational tensions to support well-being and accelerate growth and innovation in their companies. To do this, organizations must embed the practice of leadership across all levels and functions to create the conditions necessary for personal growth, actively develop emerging leaders, and focus creative energy on making internal improvements.

Author Posting. © 2009 The Design Management Institute. This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here by permission of the Design Management Institute for personal use, not for redistribution. The definitive version was published in Design Management Review, 26:3, .